The Chinese or Roundtail Paradisefish (Macropodus ocellatus) has long been regarded as a rare jewel in the aquarium. That is a great pity, as this fish has much to offer the aquarist.

The story of the discovery of the Chinese Paradisefish dates back to 1842, when Theodore Cantor of Zhoushan (formerly Tschouschan or Tschusan, English Chusan) described the new species Macropodus ocellatus. Zhoushan is a group of islands off the east coast of China. The main island was occupied by the English in 1840, 1841, and 1860 and handed back only after the opening up of China for trade with Europe. Cantor (1809-1860), a Dane by birth, was a doctor and worked as a salaried employee of the powerful East India Company, which was responsible for the occupation of Zhoushan. He was interested mainly in amphibians and reptiles, and, for example, discovered and described the King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), the largest venomous snake in the world, in 1836, but he was also very well educated in biology in general. He authored a study of the animals and plants of Chusan, published in 1842, which contained inter alia the original description of the Chinese Paradisefish. He even had a very nice water-color made of the fish, which unfortunately cannot be shown here for copyright reasons. However Hans-Joachim Paepke was able to reproduce this water-color in 1994 in his monograph on paradisefishes, albeit unfortunately only in black and white, so you don’t need to travel to London to see the original in the British Library.

The world thus ultimately has an aggressive economic policy to thank for the discovery of the Chinese Paradisefish.

Let us continue with the history for a while. In 1869 the true Paradisefish, Macropodus opercularis, was the first exotic aquarium fish after the Goldfish to reach Europe and triggered a wave of enthusiasm. Perhaps the aquarium hobby as we know it today wouldn’t exist at all were it not for the Paradisefish, but of course that must remain a matter for speculation. But the fantastic appearance of the Paradisefish also gave rise to speculation: could such a colorful fish with such luxuriant finnage really exist in the wild? Many naturalists doubted it. Because the Paradisefish, just like, the Goldfish, originated from China, it was speculated that, like Veiltail and Co, it was a form cultivated by the Chinese.

But in that case what was the original form? It was thought that it might be the species Macropodus chinensis, described by the German doctor Marcus Eliser Bloch in 1790. But unlike the Paradisefish, which has a forked tail, Bloch’s engraving shows a round-tailed fish. When, in 1913, the first Roundtail Paradisefishes became available to the general public (in fact the species had first reached Germany back in 1893, but that was kept secret) they were identified as Macropodus chinensis and given the common name of Chinese Paradisefish.

However, the Chinese Paradisefish remained largely unremarked and subsequently kept dying out in the aquarium hobby. Strange to relate, nobody wrote about the fantastic coloration of courting males.

It wasn’t till 1989 that Paepke was able to show that Bloch’s M. chinensis was just a Paradisefish with a damaged caudal fin, which is why the Chinese Paradisefish is now known to science as Macropodus ocellatus.

It wasn’t until 1983 that Chinese Paradisefishes reached Germany again, after apparently dying out completely during the Second World War. It was the Internationale Gemeinschaft für Labyrinthfische (= International Labyrinthfish Association, IGL) that managed to establish an aquarium strain, as the pet trade continued to show no interest in these fishes. Unfortunately Chinese Paradisefishes are very pale in color outside the breeding season and don’t look attractive. These first fishes for a long time were imported on private initiative. In 1984 I obtained some of the first captive-bred specimens. The gorgeous color photos of Hans Joachim Richter had aroused my enthusiasm and I had been a paradisefish fan since the 1970s when a pair of Paradisefishes spawned in one of my very first?aquaria.

Unfortunately, however, the Chinese Paradisefish proved extremely delicate. I believe that there are only a few fish species as susceptible to fish tuberculosis as Macropodus ocellatus. Fish tuberculosis is caused by a ubiquitous bacterium that can even cause skin lesions in humans under particularly unfavorable conditions – and is, by the way, the only noteworthy disease of ornamental fishes that can be transmitted to Man. It isn’t known why Chinese Paradisefishes were so susceptible to the pathogen back then. Although nobody was ever infected by them, who wants to keep fishes that sooner or later die covered in nasty ulcers? These fishes were once again in danger of dying out in the hobby. But then – and again nobody knows quite why – at some stage an aquarium strain of these lovely fishes became established that virtually never fell victim to tuberculosis. So this first recent imported strain of the Chinese Paradisefish reinforced the old saying: never give up!

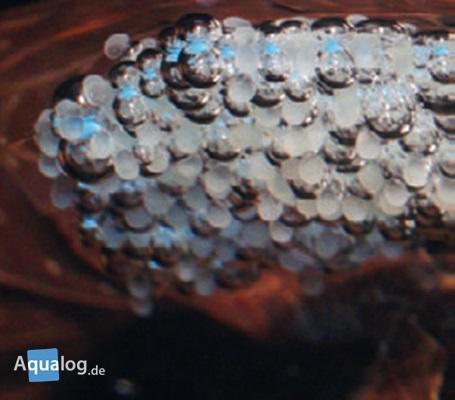

With a maximum total length of eight centimeters, the Chinese Paradisefish is a small fish. Males always grow larger than females. Sexual maturity is attained at an age of around four months, when the fishes are between three and five centimeters long. The Chinese Paradisefish is a typical bubblenest builder. The male, resplendent in his finest colors, constructs a relatively compact bubblenest. But mating is initiated by the female, who becomes a very light cream color, almost white, when ready to spawn. Outside the spawning period males and females cannot be distinguished on the basis of color. Paradisefishes produce transparent floating eggs. Mating is labyrinthfish-typical, with the male clasping the female in a U-shaped embrace, initially approaching her from beneath. Once the male has embraced the female, he turns her onto her back, and the pair release the eggs and sperm while quivering.

The young, which begin to hatch after just 24 hours, are very small. Once they become free-swimming, which begins after 48 hours (in labyrinthfishes there is always a degree of variation from early to late developers) they require some 10-12 days before they are able to take Artemia nauplii. Until then they require microscopically small live foods.

Chinese Paradisefishes are subtropical. The species distribution includes large parts of China and Korea, and they have also been introduced and become established in Japan. These fishes are sometimes found in areas where the thermometer can drop to -20 °C in winter. Hence some populations of Chinese Paradisefish are winter hardy in Europe and can be maintained year-round in the garden pond. One such population has lived for many years in an ornamental pond in front of the premises of the wholesaler Aqua-Global in Berlin. Because Macropodus ocellatus doesn’t usually live for more than three years, the fishes must also be breeding successfully there. In severe winters very large numbers die, even in the wild. Because the Chinese Paradisefish cannot breathe using its labyrinth under ice, it has to rely on breathing via the gills like normal fishes. It seems that juveniles 2-3 centimeters in length are best at surviving the winter.

Chinese Paradisefishes are strict carnivores. In the aquarium they can be fed without problem on flake, deep-frozen, and live foods of all types. The chemical composition of the water is of no importance to these fishes, although in soft water they are more susceptible to a number of parasites that prefer such water – above all Velvet Disease Piscinoodinium (formerly Oodinium).

Chinese Paradisefishes don’t require any additional heating when kept indoors. They can be maintained without problem at a temperature between 14 and 32 °C, with the regular maintenance temperature ideally lying between 20 and 25 °C, and 3-5 °C higher for breeding. It has proven very beneficial to overwinter these fishes in cold conditions for 6-8 weeks (if need be in the refrigerator). The overwintering temperature should lie between 6 and 12°C, with it being safest to work within the upper part of this range when dealing with fishes of unknown provenance.

The first step in studying a small fish species is always to establish an aquarium strain. That has been achieved in the case of the Chinese Paradisefish and at present at least the fish has sufficient fans that there is no longer any concern that it might die out in the near future. But the species has a huge natural distribution region, and, as we know from experience, local populations can differ considerably from one another. So attempts are now being made – albeit on a very small scale, as neither China nor Korea is typically an exporter of wild-caught aquarium fishes – to import wild-caught Chinese Paradisefishes from time to time and study the differences between them.

Within the labyrinthfish community it is mainly the indefatigable Thomas Seehaus that is collating all the available data on the wild forms of paradisefishes. He has also written a book on them. It is worth visiting his website at www.casa-di-lago.de !

Two years ago a wild-caught form was imported in which females don’t assume the light coloration otherwise so typical. Unfortunately, for private reasons I was unable to obtain this strain. But: never give up!

Aquarium Glaser recently imported wild-caught stocks once again, and I took a pair of these fishes home with me. Unfortunately the female developed a virulent bacterial infection. The lower half of the caudal fin and around a third of the musculature of the posterior body rotted away before the disease came to a standstill. Unfortunately the stocks at Aquarium Glaser had already been sold at this point. I had virtually no hope of the female surviving, but I did all I could to make life as pleasant as possible for her. Two handfuls of autumn leaves enriched the water with secondary plant material and the only food used was deep-frozen adult Artemia, a particularly nutritious and germ-free diet.

Two weeks later something almost incredible took place: the pair spawned. Apart from the fact that the female was dreadfully scarred and looked very incomplete, everything took place by the book. Today, as I write this article, some 150 youngsters from this pair are swimming in one of my rearing aquaria and are already somewhat more than a centimeter long.

So yet again the Chinese Paradisefish confirmed the saying: never give up!

Anzeige