The people of the western world always like to know as soon as possible if a baby is on the way. The first scientifically precise and at the same time easy-to-use pregnancy test was the clawed frogs, in this case members of the genus Xenopus. Specifically, if the morning urine of a pregnant woman is injected into the dorsal lymph sac of these species then the pregnancy hormone it contains, chorionic gonadotropin, will cause the female frog to lay eggs after 12 hours.

Xenopus laevis, the African Clawed Frog

Even before this was discovered, back in the 1940s, clawed frogs (above all Xenopus laevis) were in demand as laboratory animals. They were used to research and investigate innumerable neurophysiological and genetic principles. After the discovery that clawed frogs are suitable as reliable pregnancy tests, there was a veritable run on these animals, and so laboratory breeding became ever more important, as supplies from Africa (by ship!) weren’t quite so problem-free to acquire. It would appear that our grandparents were already fairly well aware of the value of family planning.

It was subsequently discovered that the test worked using European frogs as well, albeit not the females. In central European frogs the ripening of eggs is strictly cyclical and possible for only a few weeks per year. But, if handled correctly, males can be used to establish whether or not a woman is pregnant by the presence of strands of sperm following a urine injection.

Nowadays it is pretty unusual to find an aquarium containing clawed frogs or a terrarium of Common Frogs (Rana temporaria) in a gynecologist’s waiting room. But frog breeders all over the world use the fact that frogs react positively to human sex hormones to induce breeding when they can’t get their frogs to spawn, even when they are sexually mature. I will leave the details to the imagination of the reader…

The African Clawed Frog

If you look at the scientific and hobby literature on clawed frogs, then most of the available information concerns the African Clawed Frog, Xenopus laevis. In many cases the identification is questionable, however, as only a few people can tell the various species of Xenopus apart; six (!) new species of clawed frogs were described only recently, in December 2015! A further species (Xenopus calcaratus) has been removed from synonymy, and the number of species in the genus (including those still classified in the subgenus Silurana) is now 29 (Evans et al. 2015). But regardless of that, let us look at Xenopus laevis in somewhat closer detail.

- Xenopus laevis, Laborstamm, Männchen

- Xenopus laevis, Laborstamm, Weibchen

- Xenopus laevis, Laborstamm, auf Hand

Xenopus laevis, laboratory strain: left, male; center, female; right, in the hand.

The African Clawed Frog has long aroused the interest of humans. Xenopus means “strange foot”. In Africa people ascribe mysterious powers to these frogs. Their sudden appearance in pools after rain has led to their being regarded as rain bringers. And other myths and legends surround these amphibians.

In Europe the interest of scientists in these frogs has been more pragmatic. They have been used to research morphological and developmental physiological characteristics. In modern science they are used to produce clones (i.e. genetically identical individuals) and for other forms of genetic research. Modern gene technology was developed using clawed frogs, and nowadays the African Clawed Frog is one of the genetically most studied of all life forms.

Albino cultivated form of the clawed frog

At mating time male clawed frogs develop nuptial pads on their hands and forearms, readily visible as dark lines in this albino male.

This frog also found a place in the vivarium hobby at an early stage, as a result of, inter alia, its enormous temperature tolerance (maintenance is possible at temperatures between 12 and 36 °C, the optimum being 22 °C, however). These creatures can even be kept in unheated aquaria without problem. The first reports on maintenance and breeding appeared as early as 1905.

The African Clawed Frog (in the broad sense, the name covers several genetically different forms) has a vast distribution in Africa and inhabits practically the entire continent. There are even feral populations in Europe (Wales) and in the USA. The largest female of the nominate form captured to date measured 12.5 cm. It was found in a goldfish pond, where it had grown fat on a diet of ornamental fishes. Males always remain smaller.

The African Clawed Frog is generally adaptable and occurs in pools and ponds as well as lakes and rivers. It also lives in association with humans in garden ponds and parks. In short: it is a Jack-of-all-trades, as the saying goes. Our aquarium strains are probably no longer pure-bred subspecies. Anyone who is able to obtain wild-caught stocks should be sure to breed them true.

Leopard cultivated form.

Catfish or Frog?

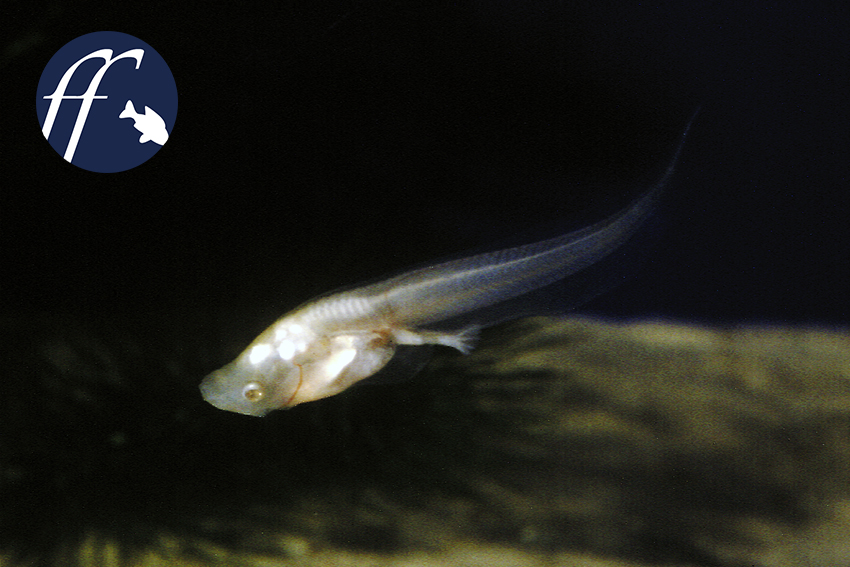

In 1864 the famous zoologist John Edward Gray described a new, unusual frog species, Silurana tropicalis, on the basis of a number of tadpoles and newly metamorphosed young frogs from Africa. The tadpoles of this remarkable creature possessed two long barbels, no teeth of any kind, well-developed eyes, a fringe of fin running around the body (as in an eel), and a second, short fin beneath the belly. None of the fins was supported by fin-rays. Gray was quite clear that it was a frog. The name of the new genus that he erected was composed of the Latin words silurus (= catfish) and rana (= frog), indicating the quite astonishing similarity to catfishes. Nobody had ever seen or described such bizarre tadpoles before. They were tadpoles of the species that we nowadays know as the Western Clawed Frog.

Larva of the albino clawed frog

A short digression on the normal appearance of a tadpole may be in order at this point. All tadpoles except those of the tongueless pipid frogs (family Pipidae, which includes Xenopus), have little horny labial teeth, arranged in strips. The tadpoles use these teeth, so characteristic in type and form, to rasp away small particles of their food, which, depending on the species, may consist of aufwuchs (the biocover composed of algae and micro-organisms coating rocks, wood, leaves, etc) and/or animal material.

Western Clawed Frog, Xenopus tropicalis.

Male clawed frogs are always smaller than females. Male behind.

The tadpoles of the clawed frogs (subgenera Xenopus and Silurana) have no labial teeth, however. They have evolved as filter-feeders, adopting a lifestyle resembling that of small fishes that feed on plankton (plankton is the term used for any small organisms that float free in the water). In addition the tadpoles of the clawed frogs also have long barbel-like threads, which really do look just like the upper-lip barbels of some catfishes (e.g. the glass catfishes, Kryptopterus).

In the wild these tadpoles swim in the open water, in shoals even. The similarity to fishes is truly amazing.

Cannibalistic breeding

Clawed frogs sometimes inhabit artificial, rather sterile bodies of water where they have established themselves outside of their natural range, for example in the USA. Investigation of what they fed on there revealed something astonishing: at certain times the stomachs of the specimens studied contained predominantly tadpoles of their own species!

Unfortunately Xenopus muelleri is an endangered species.

Portrait of Xenopus muelleri.

On the basis of comparative studies the normal diet of clawed frogs consists mainly of larger insects. There may, however, be a serious lack of food in new, barren habitats. In fact clawed frogs can endure a fast of several weeks with little problem, but in the long term even a Xenopus has to eat something now and then.

The survival strategy of clawed frogs is to bring young into the world! At first glance that may sound paradoxical, but it isn’t. The tadpoles of Xenopus are known to feed on microplankton (i.e. free-floating algae and the like),and there is hardly ever a lack of these in newly constructed artificial ponds, as many owners of garden ponds learn to their cost. Green water is a byword.

Xenopus epitropicalis, wild-caught from Nigeria.

If we consider that a single Xenopus female with a length of 6.5 cm can lay roughly 1000 eggs at a time, and a 10.5-cm long female 17,000 eggs, and that Xenopus generally spawn several times per breeding season, then it all makes sense. The result of this effort is hundreds and thousands of Xenopus tadpoles, which convert the microplankton that the adults cannot use into valuable animal protein.

Perhaps this survival technique may appear morally reprehensible from a human point of view. But it is effective, nonetheless.

Frank Schäfer

References:

Evans, B. J., Carter, T. F., Greenbaum, E., Gvoždík, V., Kelley, D. B., McLaughlin, P. J., … & Tobias, M. L. (2015). Genetics, morphology, advertisement calls, and historical records distinguish six new polyploid species of African clawed frog (Xenopus, Pipidae) from West and Central Africa. PLoS One, 10(12), e0142823.

Furman, B. L., Bewick, A. J., Harrison, T. L., Greenbaum, E., Gvoždík, V., Kusamba, C., & Evans, B. J. (2015). Pan-African phylogeography of a model organism, the African clawed frog ‘Xenopus laevis’. Molecular Ecology, 24(4), 909-925.

Additional reading material on clawed frogs can be found at https://www.animalbook.de/navi.php?qs=krallenfrosch

Anzeige

Another great example of the wonders of nature. What an interesting creature..!!